At Seattle Bookfest in late October, I found myself chatting with a gentleman at the Book Club of Washington booth about their organization. “Are you a collector?” he asked me. “No, not really,” I muttered. “Do you have more than 3 books at home?” Sure. Of course. Who doesn’t? Is it that easy to be a collector?

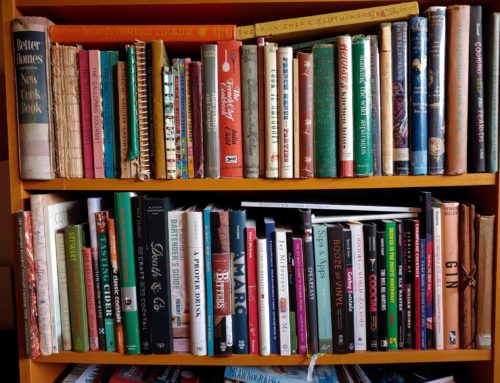

It’s surely not a fair impression, but I’ve always equated “book collector” with someone who buys volumes (often historic or otherwise singular) in pristine condition (or has them restored), then puts them on display in some elegant fashion. I sit at the other end of the spectrum. I have many hundreds of books, but they’re all over the place, some on the floor, many on shelves, some piled on the tops of said shelves. Some are new, some are old. Some are immaculate, some are verging on tattered. But it is, I suppose, a collection. If a random, unorganized, somewhat motley one.

When it comes to adding books to this collection, that’s equally random. Many show up on the doorstep, of course, as did the delicious The Grand Central Baking Book this past week. Which was delightfully frustrating only in that the book did not come with an accompanying piece of that Lemon Crumble Tart on page 126. I also received last week the new Coco book from the artfully-inclined publisher Phaidon. In it, 10 master chefs from around the world (including Alice Waters, Fergus Henderson, Ferran Adrià and Mario Batali) each picked 10 chefs they feel are on the cusp of greatness, contemporary chefs that will be tomorrow’s masters. It’s a luscious, inspiring, diverse volume that is equally cookbook, culinary narrative and travelogue, with wanderlust-inducing destinations to add to the food life list. And it was great to see Seattle’s own Kevin Davis among the chefs profiled, a choice of Mario Batali’s.

Because of the existing overload of books I already own, I don’t scour bookstores–new or used–nearly as much as I used to. Now and then, I will, unable to fully shake the habit. And I usually gravitate to the old, the quirky, the unexpected, the nostalgic. I seem to have a thing for the 1950s given the number of my books–including a Ford Motor Company collection of recipes from drive-worthy destination restaurants and Esquire’s Handbook for Hosts [my edition from 1953*]–that were published back then.

But as I first started reflecting on my oddball book collection for this post, it just happened that the first few books I reached for had a common theme. So it’s prompted me to start sharing occasional peeks at the books that surround me in this office. Starting today with the animal kingdom.

But as I first started reflecting on my oddball book collection for this post, it just happened that the first few books I reached for had a common theme. So it’s prompted me to start sharing occasional peeks at the books that surround me in this office. Starting today with the animal kingdom.

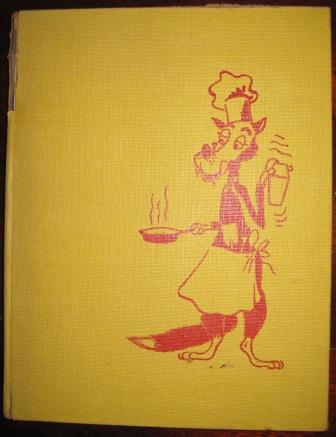

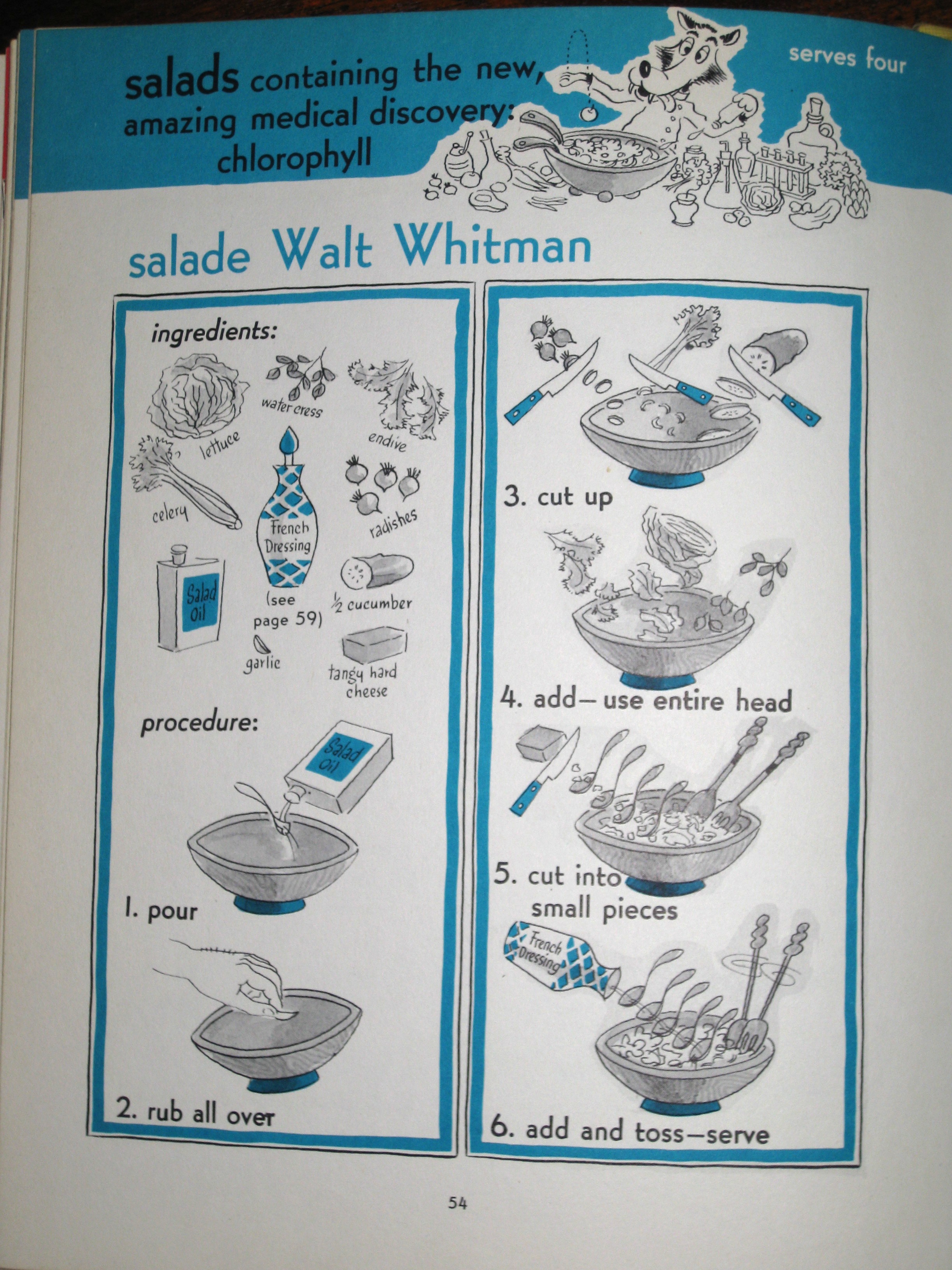

Take the Wolf in Chef’s Clothing [1950] book I picked up somewhere along the line. It was first published in 1950 by the Wilcox & Follett Co. publishers in Chicago. Billed as “the picture cook and drink book for men” (men, those wolves!!), it takes the picture-worth-a-thousand-words ideal to the extreme. Recipes never list quantities such as “2 teaspoons sugar” instead showing a sugar bowl showering its contents into two spoons. Hard to get any simpler than that! Recipes include Welsh Rabbit (rarebit, but who’s counting), C’est la Vie Canape (cream cheese-roquefort stuffed celery stalks) and even Crêpes Suzettes. Picking the book up again, I realize it bears some resemblance to the Look & Cook cookbook series I worked on with Anne Willan. Which itself was inspired in part by another volume in my shelves, La Cuisine Est Un Jeu d’Enfants (Cooking is Child’s Play). My 1965 copy includes both original and translated text, complete with forward by Jean Cocteau!

two spoons. Hard to get any simpler than that! Recipes include Welsh Rabbit (rarebit, but who’s counting), C’est la Vie Canape (cream cheese-roquefort stuffed celery stalks) and even Crêpes Suzettes. Picking the book up again, I realize it bears some resemblance to the Look & Cook cookbook series I worked on with Anne Willan. Which itself was inspired in part by another volume in my shelves, La Cuisine Est Un Jeu d’Enfants (Cooking is Child’s Play). My 1965 copy includes both original and translated text, complete with forward by Jean Cocteau!

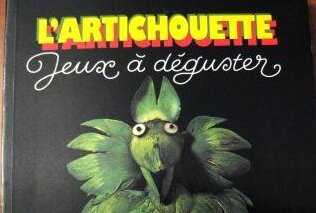

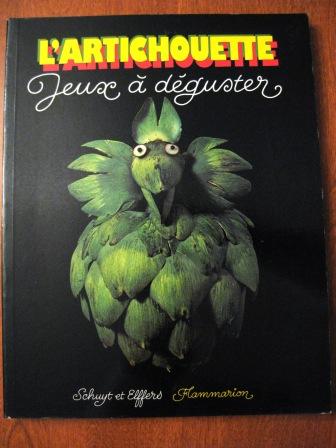

Another animalistic food book I have is less cookbook, more “food as decorative art” inspiration. L’Artichouette (which seems to be out of print)  has this wild bird-like creature on the cover, with radish-slice eyes, that exemplifies the transformations found within–in this case an artichaut (artichoke) into a chouette (owl). Get it? Arti-chouette? (Chouette is also slang for “cool,” so gets extra mileage in the title.) I picked this up in France years ago, in fact it still has the Librairie Gourmande card and facture tucked inside. The introduction references everything from the grand pièces montées of the 19th century to holiday gingerbread houses as examples of metamorphoses from food to art or structure. I haven’t tackled the carrot-race-car or palm-tree-pineapple, nor any of the creations, to be honest. It’s more a reminder of food as a source of endless artistic creativity. A more recent twist on that theme, Play With Your Food takes it to a different extreme, less manipulating the food by trimming and cutting, more finding the hidden faces, creatures and other features that fruits and vegetables naturally serve up.

has this wild bird-like creature on the cover, with radish-slice eyes, that exemplifies the transformations found within–in this case an artichaut (artichoke) into a chouette (owl). Get it? Arti-chouette? (Chouette is also slang for “cool,” so gets extra mileage in the title.) I picked this up in France years ago, in fact it still has the Librairie Gourmande card and facture tucked inside. The introduction references everything from the grand pièces montées of the 19th century to holiday gingerbread houses as examples of metamorphoses from food to art or structure. I haven’t tackled the carrot-race-car or palm-tree-pineapple, nor any of the creations, to be honest. It’s more a reminder of food as a source of endless artistic creativity. A more recent twist on that theme, Play With Your Food takes it to a different extreme, less manipulating the food by trimming and cutting, more finding the hidden faces, creatures and other features that fruits and vegetables naturally serve up.

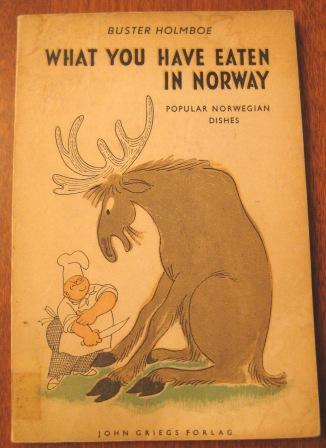

Last, a sweet, simple little book that I came across in the vast cookbook collection at Château du Feÿ when I was helping Anne Willan determine how to prioritize the 4,000-plus cookbook library there prior to their move. A few books that ended up in up-for-grabs pile caught my eye, this one included. I mostly loved the title, since I haven’t been to Norway and have not, in fact, eaten anything there. And the determined look on that chef’s face. Inside, most recipes are in that very simple brief-paragraph narrative form, including fylt kaalhode (stuffed cabbage) sursild (sour pickled herrings) and risengrøt (rice porridge).

Last, a sweet, simple little book that I came across in the vast cookbook collection at Château du Feÿ when I was helping Anne Willan determine how to prioritize the 4,000-plus cookbook library there prior to their move. A few books that ended up in up-for-grabs pile caught my eye, this one included. I mostly loved the title, since I haven’t been to Norway and have not, in fact, eaten anything there. And the determined look on that chef’s face. Inside, most recipes are in that very simple brief-paragraph narrative form, including fylt kaalhode (stuffed cabbage) sursild (sour pickled herrings) and risengrøt (rice porridge).

Motley, indeed, these books I surround myself with. And with my office redo imminent, I’ll be pulling each and every one from its shelf for safe keeping while floor, walls and new furniture are attended to. Seems an ideal time to purge a few from the collection. But my money’s on 99 percent of the books coming back to the new shelves. Old or new. Quirky or not. There’s something to relish in every single one of them.

* I offer links to older books as available, though these often represent reproductions of the original volumes. I think it’s far more fun to have a copy that dates to or near the time of original publication. More authentically nostalgic with its yellowed pages, dog-eared spine, likelihood of having passed through the hands of at least a few cooks and hosts over the years.