If you’re writing recipes more than occasionally (heck, maybe even if just occasionally), it’s great to build up a collection of resources to have at hand: places to turn when you’re unsure about how to reference a specific ingredient, how to approach organizing the technique steps, how to spell panzanella (which autocorrect wanted to capitalize just now, by the way, proving not all resources are in sync about the best approach—a common theme to get comfortable with).

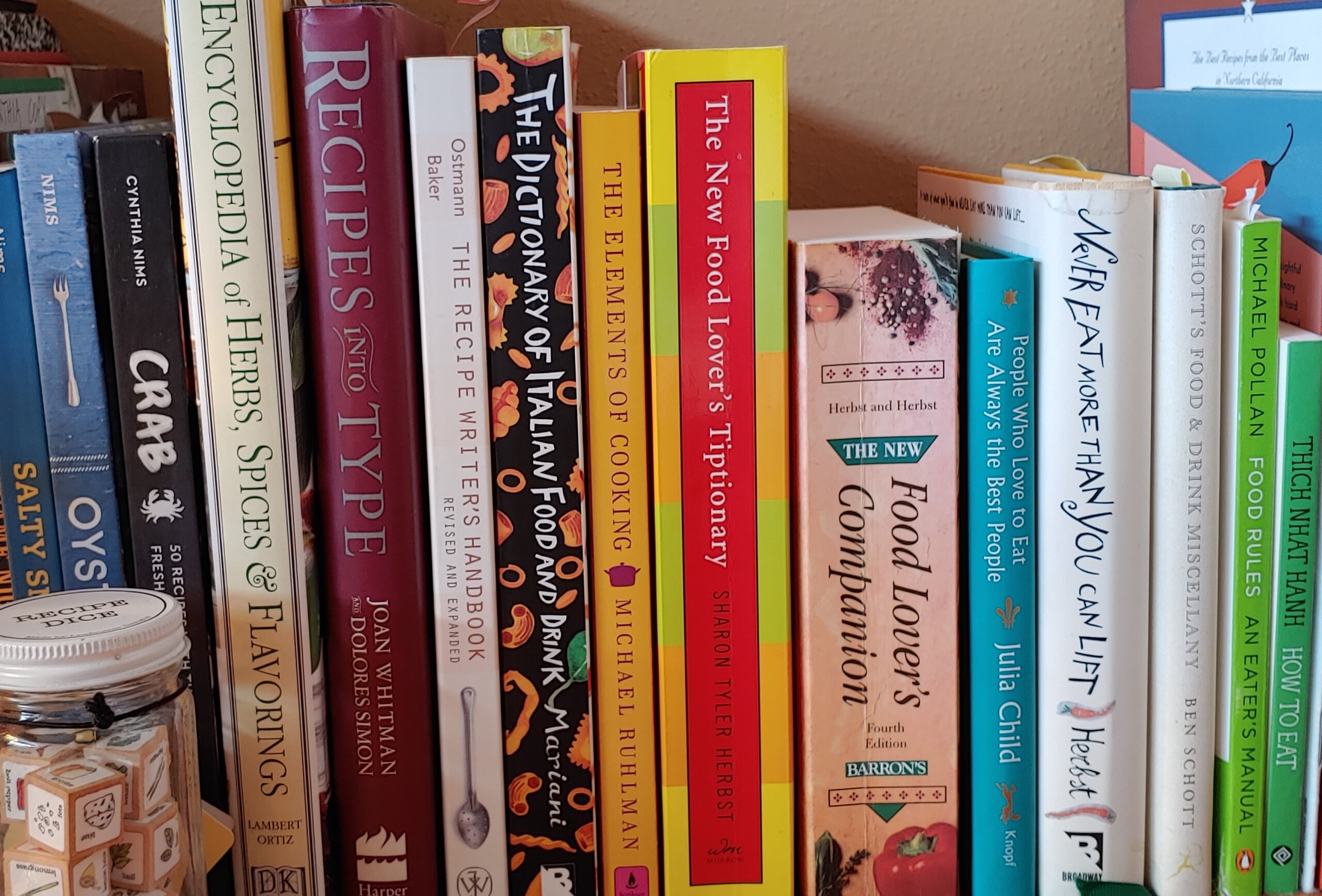

Some of the books that I’ve turned to most often when writing recipes over the years include The New Food Lover’s Companion, The Recipe Writer’s Handbook, and Recipes Into Type. These are pretty common on many recipe-writer’s shelves. And a good ol’ dictionary, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate is the frequent go-to. To a lesser degree, when contemplating details for a specific ingredient, I also pull out The New Food Lover’s Tiptionary.

Though really, the hundreds of books that surround me right now in my office are a wealth of recipe-writing resource. Some are more intentionally created as reference material, such as The Dictionary of Italian Food and Drink, The Encyclopedia of Herbs, Spices & Flavorings, or The Elements of Cooking, just a few among many such titles. I turn to my cookbooks for everything from initial inspirations of flavors and combinations to consider, to technical aspects of cooking process and handling ingredients, to broadening my skills in the descriptive language of recipes.

As hinted at earlier, when it comes to specific recipe style elements—the practical details of how you express what needs to be said in the recipe—not all recipe resources agree. In part because there simply aren’t hard and fast rules on many recipe elements. And there’s a lack of absolute agreement in all cases for spelling, capitalization and other of the more mundane details to be considered. This is where a personal style guide becomes a valuable resource to add to your tool kit. It will be a subject for another day (or two, or three), but as you develop more and more direction with your own approach and preferences, your own guide becomes a prime resource, relying a bit less on others.

I’m intrigued that the two recipe-writer reference books, The Recipe Writer’s Handbook and Recipes Into Type, are still the prime options of their category so many years after their publication. The former is newer, but even that’s a 20-year-old book. And the one I more often see mentioned on current-day style guides is the latter, nearly 30 years old.

I suppose those books’ continued relevance reflects that much about the nuts and bolts of quality recipes remains the same. And your personal style guide will, over time, fill in gaps and update whatever details are more currently appropriate. As I did mine, recently, after an editor pointed out the benefit of now specifying “canned coconut milk,” with the newer potential for confusion with the coconut version of alternative milks.

We’re never done fine-tuning this craft of recipe writing. It is in a constant evolution. Not only in that joyful exploration of creating new dishes to share, also in the language and structure we use to artfully, accurately convey that new creation in recipe form. Having diverse and reliable resources at hand helps a great deal.

By no means an exhaustive list, just recapping books mentioned above:

The New Food Lover’s Companion, by Sharon Tyler Herbst and Ron Herbst, 2007, Barron’s Educational Series

The New Food Lover’s Tiptionary, by Sharon Tyler Herbst, 2002, William Morrow and Company, Inc.

The Recipe Writer’s Handbook (Revised and Expanded), by Barbara Gibbs Ostmann and Jane L. Baker, 2001, John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Recipes Into Type, by Joan Whitman and Dolores Simon, 1993, HarperCollins Publishers

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th Edition

The Dictionary of Italian Food and Drink, by John Mariani, 1998, Broadway Books

The Encyclopedia of Herbs, Spice & Flavorings, by Elisabeth Lambert Ortiz, 1992, Dorling Kindersley, Inc.

The Elements of Cooking, by Michael Ruhlman, 2007, Scribner